Written by Dr. Gail Dines, a Professor Emerita of Sociology and Women’s Studies

In the 1970s and 80s, feminists argued that prostitution could not be separated from porn, or as Andrea Dworkin so succinctly stated, “porn is prostitution with the camera going.”[i] Over the ensuing decades, however, there have been both theoretical and political attempts to disentangle porn from prostitution, leading to a truncated analysis of both porn and prostitution. In this discussion, I am using the terms “prostitution” and “trafficking” interchangeably because, as Farley writes, “More than 80% of the time, women in the sex industry are under pimp-control, that is what trafficking is.”[ii]

Moreover, “Pornography also meets the legal definition of trafficking if the pornographer recruits, entices, or obtains women for the purpose of photographing live commercial sex acts.”[iii] Beyond the legal perspective, the linkages between porn and trafficking go much deeper.

To better understand the linkages between porn and trafficking, and how they are similar in some respects (and different in others), the business concept of “value chains” is useful. Value chains refer to the whole range of activities involved in making and selling a product or service, from sourcing components to production, distribution, and consumption. The idea of the value chain is that “value” is added at each stage, though the term “harm chain” is more appropriate for porn and trafficking, because each stage causes harm to women—the sex industry’s “product.” Only the companies and pimps involved make a profit.

The first link in the harm chain is recruitment.[iv] In terms of porn and trafficking, this means grooming and enticing women into the sex industry. Studies show that the recruitment of women into both porn and trafficking relies on the same dynamics. On a macro-level, the most powerful recruiter is a hyper-sexualized porn culture that socializes girls and women to self-objectify and self-sexualize. Yes, it is the culture that grooms girls and women to be pimped into porn and prostitution. As Joanna Angel, a hardcore pornography producer and performer, told Details magazine, “the girls these days, just seem to come to the set porn-ready.”[v] In a similar vein, an incarcerated child-rapist told me in an interview that grooming his ten-year-old step-daughter, whom he later went on to rape, was not difficult because “the culture did lot of the grooming for me.”[vi]

Both the pornographer and the rapist, working from the same “playbook,” recognize and harvest the power of the pornified visual landscape to indoctrinate girls and women into a patriarchal mindset that the only way to be visible— in fact valuable— is to be sexually desired, “hot,” and pornified.

The pimps entice women and girls into the porn industry with promises of becoming a celebrity, with the attendant wealth and visibility this affords. They point to the sex-tapes of celebrities such as Paris Hilton and Kim Kardashian that jump-started both women’s climb to fame.

What the pimps fail to point out is that because these women are extremely wealthy celebrities, leaking a sex tape actually amplifies their fame and fortune. If these women were poor and unknown, they’d be saddled with the term “slut” and their lives, as studies have shown, would be upended. And women of color suffer even greater social humiliation and degradation.

The promise of wealth is a powerful form of enticement because the majority of women in the sex industry are poor, and in an ever-growing world of income inequality, have few choices to move up the socio-economic ladder. Women of color are especially at risk of poverty being poor because of the systemic racism that limits access to good schools and job-training programs.

Probably one of the most powerful factors that drives women into the sex industry is, as Donevan argues, childhood sexual abuse. Donevan found this to be “the most common precursor to prostitution, with studies finding that between 60-90% of prostituted persons have been subject to sexualized abuse in childhood.”[vii] Donevan points to a study by Grudzen et al.,[viii] that found that women in porn were three times more likely to have been victims of childhood sexual abuse compared to women who were not in porn.

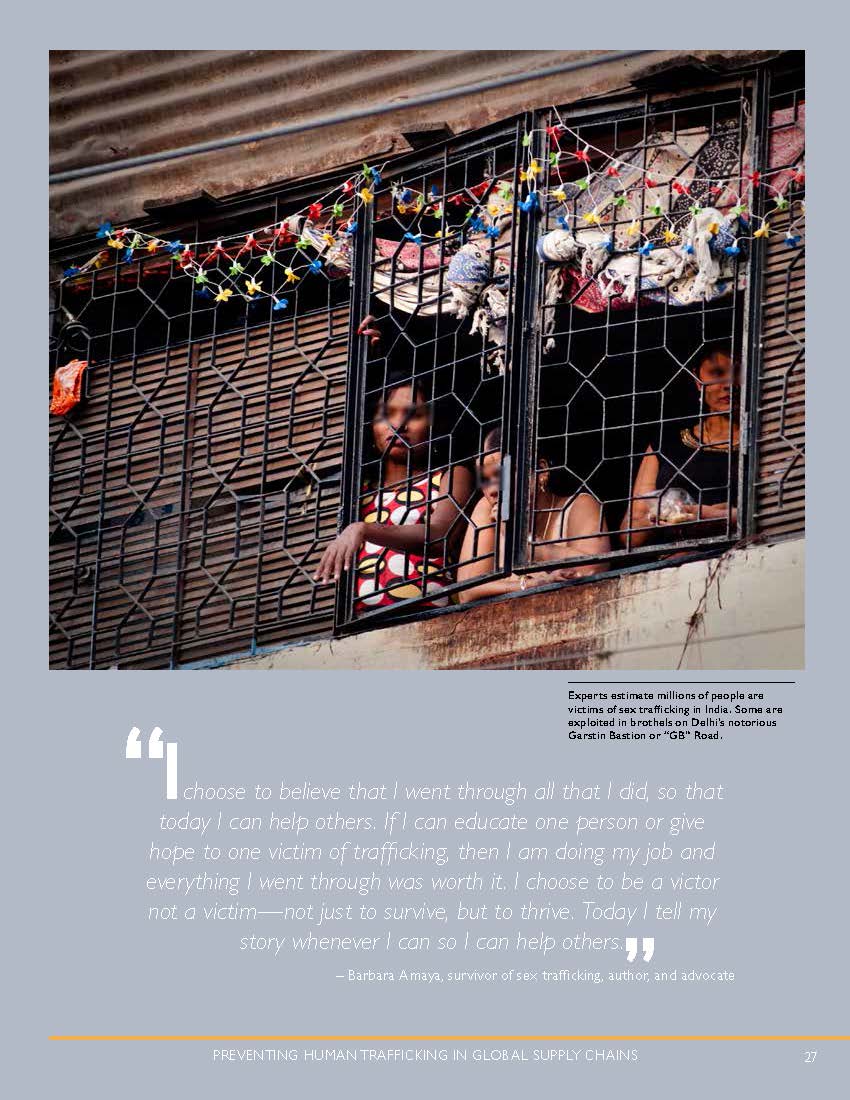

The “product” of both porn and prostitution is the sexual exploitation of women. The only other industry where the product is the buying and selling of human bodies is slavery, which is why survivors and their allies call the sex industry sexual slavery, not “sex work.”

Men pay for the experience of sexually degrading and debasing a woman, turning her, in their minds, into a “whore” who is deserving of sexual violence. The consumers simultaneously construct, cement, and bolster their sex-class power, as they produce and reproduce women as an oppressed class in the patriarchal relations of production. The monetization of women as “product” is different in porn compared with prostitution, because porn images and videos are mass-marketed and distributed online on an industrial scale through multinational conglomerates such as Mindgeek.[ix]

The chain of harms women suffer in pornography and prostitution have been well documented.[x] Moreover, these harms are not unfortunate “byproducts,” but are central to the value (sexual pleasure) to the user. The more brutal, cruel, and violent the “sex” act, the more the users feel as though they got their money’s worth. Reading the Adult DVD Talk forum, a website where porn users discuss their favorite scenes, makes clear just how much users are indeed on the lookout for scenes where the woman is suffering real pain. A popular thread—called Painful Anal—has numerous posts where fans list their favorite scenes and discuss at great length their enjoyment at watching the woman cry, scream, or show fear.

Once in the revolving door of the sex-industry, the women often end up even poorer than when they started. Lack of health care benefits means that women have to pay out of pocket for treating STIs, bodily injury, and PTSD. The now-shuttered Adult Industry Medical Health Care Association, which was the Los Angeles-based voluntary organization in charge of testing porn performers, had a list on their website of possible injuries and diseases to which porn performers were prone. These included HIV; rectal and throat gonorrhea; tearing of the throat, vagina, and anus; and chlamydia of the eye. Not your everyday workplace ailments, unless, of course, you are being prostituted, on or off camera.

The distribution end of the harm chain for pornography used to look very different from prostitution. The former requires an ecosystem of websites producers, directors, filmmakers, webmasters, web-based payment systems, and distribution networks. Prostitution, on the other hand, was typically a more low-tech and leaner value chain, in which production and consumption were two aspects of the same sexual act— the buying and selling of women.

However, pornography and prostitution are becoming even more inseparable today with the growing popularity of sex camming, where (mostly) women livestream sex acts for men who pay for private shows.[xi] One of the most popular sex-camming sites is Chaturbate, with an estimated 18.5 million unique visitors, just in the US, and has an Alexa rank of 21. Chaturbate, like the other sex-camming platforms, plays the role of pimp by taking 50% of the women’s earnings. It also has a “referral” system where affiliates receive $50 per “model” who signs up via the affiliate site, thus expanding the chain of pimps.

The concept of harm chains is generally used to suggest how harms from making and distributing products such as clothes and coffee can be reduced or minimized. None of these suggestions on how to reduce harm apply to the sex industry. The very nature of this industry is to create harm on the micro level–to the women’s and girls’ bodies–and on the macro level, the normalization, glorification and monetization of sexual violence. The sex industry inherently and irredeemably reinforces a culture and economy that victimizes and subordinates women and girls as a sex-class. The only way to stop the harm chain is to close down the sex industry. Only this will enable women and girls to live a full life in which their civil and human rights are fully valued.

Dr. Gail Dines, a Professor Emerita of Sociology and Women’s Studies, is President of Culture Reframed, a research-driven non-profit dedicated to building resilience and resistance in young people to porn culture. She is the author of Pornland: How porn has Hijacked our Sexuality, (Beacon Press), which has been translated into five languages, Her TEDx talk can be seen here.

[i] Speech given by Andrea Dworkin at the “Sexual Liberals and the Attack on Feminism” Conference, NYC, April 6th, 1987

[ii] Farley, Melissa & Donevan, Meghan (in press, 2021).

Reconnecting Pornography, Prostitution, and Trafficking: ‘The experience of being in porn was like being destroyed, run over, again and again’

Atlánticas, an International Journal of Feminist Studies, 6 (2)

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] For a more extended discussion of recruitment into the sex industry see Donevan, M. (2021). “In This Industry, You’re No Longer Human”: An Exploratory Study of Women’s Experiences in Pornography Production in Sweden. Dignity: A Journal of Analysis of Exploitation and Violence, 6(3), 1.

[v] Details Magazine, February, 2010.

[vi] For a more detailed discussion, see Dines, G. (2010). Pornland: How porn has hijacked our sexuality. Beacon Press. Chapter Six: Visible or Invisible: Growing up Female in a Porn Culture

[vii] Donevan, ibid.

[viii] Grudzen, C. R., Meeker, D., Torres, J. M., Du, Q., Morrison, R. S., Andersen, R. M., & Gelberg, L. (2011). Comparison of the mental health of female adult film performers and other young women in California. Psychiatric Services, 62(6), 639-645.

[ix] For further discussion of MindGeek see Dines, G, “There is no such thing as IT”: Toward a Critical Understanding of the Porn Industry. In Brunskell-Evans, H. (Ed.). (2017). The Sexualized Body and the Medical Authority of Pornography: Performing Sexual Liberation. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

[x] See, for example, Moran, R. (2015). Paid for: My journey through prostitution. WW Norton & Company.

[xi] https://nordicmodelnow.org/2020/10/24/3-dangerous-myths-about-webcamming-debunked/

Today, the U.S. Department of State released the 15th annual

Today, the U.S. Department of State released the 15th annual